Expanding Diversity in New York State's K-12 Leadership Pipeline

Challenges and Solutions, by Region

Margaret Terry Orr, Professor

Department of Educational Leadership, Policy, and Instructional Practice

College of Education and Human Development

Stony Brook University

Miranda Kane, Research Assistant

Educational Leadership Doctoral Program

Stony Brook University

December 2024

This work was supported by a grant from the New York State Education Department. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the New York State Education Department.

Table of Contents

- Abstract

- Prior Analysis of the K-12 Leadership Pool

- Purpose: Expanding Research to New York's Regional and Local Level

- Research Methods and Data Sources

- Results of Town Hall Discussions: Challenges

- Results of Town Hall Discussions: Recruitment Solutions

- Results of Town Hall Discussions: Retention Solutions

- Significance of This Work

- Epilogue: Other States Diversifying Their Educational Leadership

- References

Abstract

Across the country, educator diversity is not keeping pace with student diversity. This is especially true for school and district leaders. In New York State, a 2021 study found that of the 40 percent of students who are students of color, only 10.6 percent of superintendents and 18.5 percent of principals are persons of color. Less than a third of principals and superintendents are women. The 2021 study also identified challenges and solutions to expanding diversity in New York State's K-12 leadership pipeline. However, because New York State is so diverse, there was a need to expand upon the findings of this statewide analysis at a regional level.

To learn more about regional differences in challenges and solutions to expand diversity in New York's educational leadership pipeline, the research team held six regional Town Hall discussions around the state over the summer of 2024. Over 140 educational leaders, school board members, policy makers, members of professional educator organizations, and professors participated in the conversations. The team asked participants to identify priority regional challenges and solutions to expanding leadership diversity in their region.

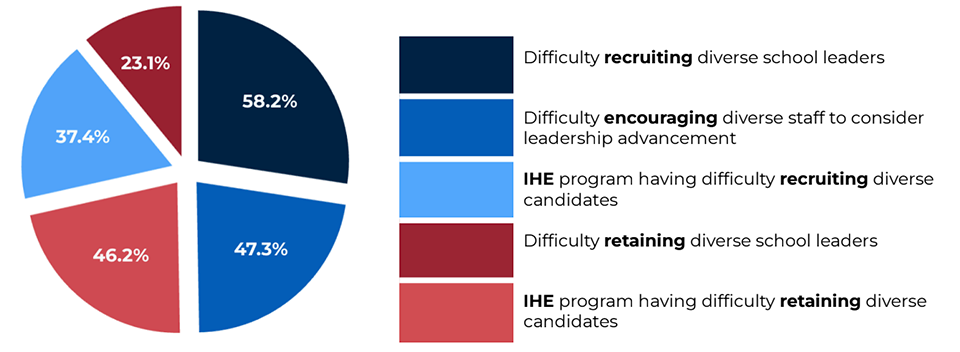

Across the six regions, participants identified five major challenge areas and a set of solutions to address them, organized under two approaches: recruitment and retention. The identified challenges mirror those identified in the statewide analysis and reinforce them with regional specifics. The recruitment solutions involve both spreading information about the opportunities and value of educational leadership roles, and developing pathways and supports for people of diverse backgrounds and from underrepresented groups to enter into and complete educational leadership preparation programs. The retention solutions involve two prongs: systemic changes and more individualized supports for leaders from underrepresented groups. These findings provide direction for state and regional educational leadership stakeholders.

Prior Analysis of the K-12 Leadership Pool

In 2021, researchers at Bank Street College, CUNY, and Stony Brook University conducted a landscape analysis of educational leadership preparation in New York State. The analysis was based on publicly available data from the New York State Education Department (NYSED) and from surveys of preparation program directors, program candidates and graduates, and sitting New York State school leaders. The analysis found that New York has a leaky leadership pipeline at every stage. That is, many who start on the pathway to becoming a school leader do not finish, and those who finish do not last long in the role. The leaky pipeline is shown in the following progression:

As part of the landscape analysis, the research team also examined the demographic characteristics of school leaders, compared to their students. For the 2018-19 school year, students of color comprised approximately 40 percent of the student population. However, only 10.6 percent of superintendents and only 18.5 percent of principals were persons of color. Moreover, of the 18.5 percent of principals of color, most (75 percent) worked in New York City or the "Big 4" cities (Buffalo, Rochester, Syracuse, and Yonkers). That is, in the rest of the state, persons of color represented only 8 percent of principals and less than 4 percent of superintendents.

The landscape analysis also found that less than a third (31.1 percent) of superintendents and principals in New York State are women. And, although New York State's population of students with disabilities is 20 percent, less than 2 percent of New York State's superintendents and principals report having a disability.

Through surveys of New York State school leaders and interviews with candidates and graduates of educational leadership preparation programs, scholars examined reasons for the leaky pipeline and the lack of diversity in school leadership. They found several challenges, organized into three categories: systemic and cultural challenges, financial and time challenges, and program design challenges. The landscape analysis also identified a set of possible solutions for addressing these challenges and expanding diversity in educational leadership, ranging from changes in state and program policies to more targeted, individualized supports. However, because New York State is such a diverse state, there was a need to expand upon the findings of the statewide analysis at a regional level.

Purpose: Expanding Research to New York's Regional and Local Level

The purpose of this follow-up analysis is to expand upon the statewide findings and recommendations from the 2021 landscape analysis. The two research questions are:

- What are the priority regional challenges to expanding the diversity of the K-12 leadership pipeline in New York State?

- What are promising regional solutions to address these challenges and expand diversity in the K-12 educational leadership pipeline?

Research Methods and Data Sources

To learn more about regional challenges and solutions to expanding diversity in New York's educational leadership pipeline, the research team held six regional Town Hall discussions across the state over the summer of 2024. Over 140 people participated in the Town Halls, including superintendents, principals, assistant principals, aspiring principals, school board members, members of professional educator organizations, policy makers, and professors.

The research team used three approaches to get the word out about the Town Hall discussions:

Partner with regional educational leadership associations

The team shared a flier about Town Halls with the directors of regional New York State Council of School Superintendents (NYSCOSS), School Administrators Association of New York State (SAANYS), and New York State Association of School Business Officials (NYSASBO) chapters and asked them to share the information with their members.

Engage graduate programs

The team contacted faculty at local graduate schools of education and asked them to share Town Hall information with their graduate students.

Publicize broadly

The team advertised Town Halls on social media, through listservs, and asked members of the New York State School Leadership Task Force to share information through their networks.

Participants

Across the six regional Town Halls, 142 people participated in the discussions. As shown in Table 1, each Town Hall had at least 14 participants and as many as 38. The Town Halls in the North Country, Central New York, and Finger Lakes regions had the most participants. Demographics of the participants are available in Appendix A and Appendix B.

| Region | Location | Participants |

|---|---|---|

| North Country | Plattsburgh | 38 |

| Capital District | Albany | 14 |

| Central New York | Syracuse | 30 |

| Finger Lakes | Rochester | 29 |

| Western New York | Buffalo | 15 |

| Long Island | Stony Brook | 16 |

| Total | 142 |

Town Hall participants represented a range of roles and perspectives (see Appendix A). Most participants (40 percent) were current school or district leaders (superintendents, assistant superintendents, principals, and assistant principals). Over a third (37 percent) were aspiring administrators, either currently enrolled in educational leadership preparation programs, or individuals interested in exploring school leadership roles. School board members comprised 5 percent of participants, and the remaining 18 percent held diverse positions, including central office administrators, regional BOCES staff, professional organization leaders, and professors.

The team asked participants why they came to the Town Hall (see Figure 1). Just over half of the participants (53 percent) came to learn about current challenges and possible solutions to expanding diversity in New York's educational leadership. About a fifth of the participants (19 percent) came to connect with others interested in expanding diversity in school leadership. Another fifth (21 percent) came to share their personal experiences and advocate for greater representation in educational leadership. A small number (7 percent) reported attending to support someone else who was participating in the Town Hall.

Figure 1: Participant Motivations for Attending Town Halls

Figure 1: Participant Motivations for Attending Town Halls

| Motivation | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Learn about challenges and solutions | 53% |

| Share personal experiences and advocate | 21% |

| Connect with others | 19% |

| Support someone else | 7% |

Town Hall Format

Each Town Hall followed the same format. Members of the research team welcomed participants and introduced the Town Hall goals and format. The team then presented key findings from the 2021 landscape analysis of the K-12 leadership pipeline (described above). After the presentation, participants broke into small groups to discuss the following questions:

- What are the priority challenges to expanding diversity in your region?

- What are promising solutions to address these challenges?

Each small group had a facilitator and a note taker. Facilitators guided the discussion and ensured that all voices were heard. Note takers recorded the key points from the discussion. After the small group discussions, the full group reconvened, and each small group shared their top challenges and solutions. The research team recorded these full group discussions.

Data Analysis

The research team analyzed the notes and recordings from all six Town Halls. The team used a thematic analysis approach to identify common challenges and solutions across regions. The team first reviewed all notes and recordings to get a sense of the overall themes. They then coded the data, identifying specific challenges and solutions mentioned by participants. Finally, the team organized the codes into broader categories and themes. Throughout the analysis, the team looked for both commonalities across regions and unique regional perspectives.

Results of Town Hall Discussions: Challenges

Digging deeper, we analyzed recorded group notes for leaky spots in the pipeline—areas within or between pipeline segments where diverse candidates tend to fall off or are not well-represented in the first place. We discovered five trouble areas common to most participants' schools, districts, and programs:

Inadequate Candidate Pool

Several participants commented that there is a general lack of qualified candidates, which suggests a need to "prime the pump"—or find ways to draw more people into the profession so that more potential leadership candidates emerge from teaching. The group from the Indigenous Nations region pointed to a lack of diversity in their pool, describing it as too narrow, or one small pool of candidates for too many schools.

"We [in the Indigenous Nations region] are all trying to recruit from the same small pool. We need to enlarge the pool of potential candidates."

(Quote from recorded group notes)

Insufficient Candidate Readiness

Others focused on the role of higher education preparation programs. Some shared a need for candidates' to have more exposure to and practice with what it is really like to work across various districts and school settings during their time in a preparation program. Some shared specifically that candidates' internships should ensure comfortability with a variety of settings doing the real work of leading a school community. Overall, there's a need for new leaders to be better prepared to take on their roles.

"Experience…the work and skills needed [for] K12 practice is critical to creating leaders who are prepared for their work in a variety of settings."

Gaps Between Preparation and Recruitment Segments

Several groups focused on gaps between segments in the pipeline, particularly between higher education preparation programs and school districts. Some shared that universities should provide more recruiting help to districts or do a better job of recruiting diverse candidates into their programs.

"Colleges have to provide infrastructure and support to departments so that intentional and on-the-ground recruitment can be done."

Limitations in Recruitment Efforts

Finally, a few groups were very critical of some school districts' general recruitment practices, describing them as a hindrance, weak, too narrowly focused, and too reliant on conventional strategies. Some focused on district culture and possible bias embedded in recruitment methods, such as:

- Not enough structure within the process to encourage diverse applicants towards the district;

- A lack of understanding of how to create a welcoming environment for a diverse candidate or new hire;

- "Culture wars" from the school community regarding the hiring of diverse leaders.

"Non-minority people view the hiring and recruitment process with a narrow lens."

"Screening Interview, Committee's Implicit Bias, Culture Shock for hired diverse leaders."

Barriers to Long-Term Retention

A few groups noted regional differences in retaining diverse hires—that regions with higher diversity among the student and teaching populations tend to have more success recruiting and retaining leaders of varying demographics. For more racially homogenous districts, structural and bias-related factors may contribute to recruiting and retention challenges.

"Some districts with diverse populations are better able to attract diverse candidates than districts with less diverse populations."

Results of Town Hall Discussions: Recruitment Solutions

Turning to how to begin to solve these persistent barriers to success, the groups looked for pathways forward: what has gained footing in the past in certain districts or programs and what new methods might make a positive impact. The areas explored closely related to challenges these stakeholders face everyday; key suggestions fell into five buckets:

Increase Recruitment of Diverse Candidates at IHEs

Several groups proposed methods for expanding the pool of aspiring leaders of color, mainly within school districts or during preparation programs. Within leader preparation programs at IHEs, the focus is on methods to increase recruitment of diverse leadership candidates. Ideas include:

- Easing the transfer of educational leadership master's credits into doctorate programs for education.

- Providing tuition discounts, scholarships or other financial support.

- Using a peer recruiter system.

- Creating thematic leadership preparation programs, such as math leadership or leadership for non-public schools.

- Encouraging teacher leaders to pursue initial certification.

- Market leader preparation programs through social media platforms.

Develop "Grow Your Own" Programs To Empower Teachers

Within schools, the focus is in "grow your own" programs—formal structures that encourage teachers of color towards school and district leadership. The programs generally help teachers gain leadership experience while still in the classroom and encourage them to pursue leadership opportunities through internal pathways at their school. Successful initiatives have included:

- In Kenmore-Town of Tonawanda (Ken-Ton) School District: A grant-funded program pairs mentor teachers with newly hired teachers called interns. While expensive, the program helps to strengthen pedagogical practice and teacher retention, while developing "master teachers."

- In Williamsville School District: Team teaching that pairs teacher leaders with less experienced teachers called interns. Mentors gain leadership experience and interns gain a net of support and improved instructional practices.

- Some districts have forged connections with specific university programs to create an easier jump between a teacher's pursuit of leadership within the school to a leadership preparation program and certification.

Address Structural Barriers in the Pipeline

While suggestions for districts and IHEs are aimed at supporting teachers of color in the pursuit of school and district leadership, some groups also broadened their discussion to touch on systemic structural barriers at the state level. Recommendations for addressing structural barriers at the state level include:

- Modifying licensure requirements to increase accessibility to K-12 leadership, such as reducing or removing teaching requirements for leader candidates.

- Offering tuition discounts to leadership preparation programs for candidates of color (e.g., University of Rochester's reduced tuition program).

- Addressing possible bias in district-level screening and interviewing processes.

Shift Prep Programs Towards a Multicultural Approach

Some groups discussed ways to strengthen leadership preparation programs to better prepare aspiring leaders to succeed in districts that may or may not mirror their own demographic makeup:

- Add coursework on developing a welcoming, inclusive community.

- Provide more authentic experiences during coursework and internships.

- Add coursework on power, privilege and identity to help aspiring leaders navigate the diversity challenges they might face as new leaders.

- Offer coursework across more instructional modalities to engage more candidates.

- Make leadership preparation programs more realistic; include actionable assignments that can be practiced despite time constraints.

- Provide candidates with proper training—specifically field work that mirrors the real job—to help them be successful. An experience-based strategy helps candidates to be more prepared on their first day on the job as they begin leading staff and supporting students.

- Provide pathways for candidates to accomplish their field work across multiple schools and districts.

Form or Strengthen District ↔ Higher Ed Partnerships

Among groups, the most prominent suggestion was to form or strengthen partnerships between districts and universities to foster the recruitment of the brightest students into IHE preparation programs. The following partnerships were noted as successful and impactful to diversifying the K-12 leadership in New York State:

- Hofstra University, Fordham University and others form local advisory councils to build relationships with local districts.

- New York City districts partner with NYC Men Teach.

- Syracuse University does outreach to local organizations for a "grow your own" program.

- Urban Alliance works with districts in upstate New York to foster leaders of color through diversity, equity, and inclusion work and culturally responsive education work.

- Erie 1 BOCES superintendents nominate teachers to a leadership pipeline program, pre-qualifying them for program enrollment.

- New York City District 6 partnership with City College to support "grow your own" type programs.

- The University of Rochester partners with BOCES to enable candidates to take graduate courses at BOCES, University of Rochester, and other IHEs, and accepts those credits.

Moving from recruitment, groups also discussed how to support and retain leaders once on the job for long-term success across varying school and district contexts.

Results of Town Hall Discussions: Retention Solutions

Moving from recruitment, groups also discussed how to support and retain leaders once on the job for long-term success across varying school and district contexts. Groups proposed retention strategies centered around bolstering new leaders' capacity to succeed and adjusting the system to retain a more diverse pool of K-12 school and district leaders and leader candidates. A note from one group emphasizes the central idea—"this is a systemic problem that requires a systemic solution." Proposed strategies fall into two main prongs:

Create Structural Support Networks

Most suggestions focused on finding the best ways to strengthen connections among K-12 leaders. These connections are seen as the main pathway to build support networks for new leaders and leader candidates. They also represent an opportunity for new leaders to build social capital, helping them in turn effectively influence and impact their school, district, and region. Groups offered three ways to create structural support for K-12 leaders:

Build Mentoring Programs

Groups suggested varying forms of mentoring pairs within or across districts: new leaders with experienced leaders; peer leaders entering their roles; and leaders of similar demographics. Groups discussed the length of the mentoring period, ideas to pair by content, and ways to make virtual networking impactful.

Facilitate Networking

Groups suggested proactively working with regional and statewide professional associations of diverse leaders to foster connection. A few participants went further to recommend creating a regional network of diverse leaders.

Foster Affinity Groups

Groups suggested creating affinity groups for more sustained, informal professional and personal support and learning among leaders of diverse demographics and backgrounds. These networks could function as low-key support groups or organize into a more formal cohort to explore various school settings and ways of leading, such as visiting different schools and communities.

In exploring models for connection, groups tended to discuss what would help these networks function well and stay organized over time for greater impact to New York's K-12 leadership pool.

Collaborate Closely at the Regional Level

Groups agreed that organizing structural support networks at the regional level would most likely yield lasting impact—rather than at the local or state level. Regions tend to share similar challenges, successes, and population demographics, yet are large enough to organize substantial groupings of K-12 leaders of all different types—leader candidates, new leaders, and experienced leaders, of varying racial, ethnic, gender, and other demographics. (Some denser regions, such as NYC, organize in different ways, of course.) Regions are also large enough to connect not only school districts but also regional professional associations, affinity groups, and institutes of higher education. Collaboration at the regional level across these groups is likely to better prepare leader candidates to begin work and new leaders to succeed on the job both personally and professionally.

Significance of This Work

Long term, diversifying K-12 leadership in New York State begins by planning and supporting career advancement for a more diverse staff, from teacher aides to teachers and leaders, and supporting their retention and advancement along the leadership career trajectory. A recommendation for three steps to remove barriers and open up pathways that came out of our Town Hall discussions are:

- Enlarge the pool of diverse candidates with purposeful recruiting from districts and institutions of higher education.

- Build structures and processes to screen and interview candidates that are fair and culturally sensitive.

- Apply a range of efforts to retain a diverse K-12 leader pool that are responsive to varying issues, district context, and responsibilities, but include mentoring and support practices.

These recommendations and other points in the Town Hall discussions invite three paradigms about how to approach diversifying the leadership pipeline: a social capital perspective, a systems perspective, and Critical Race Theory. Approaching the issue with these as an organizing framework expands the focus from what individual institutions of higher education and individual school districts can do to how to coordinate more strategic efforts among them regionally and statewide for greater impact.

A social capital perspective (McCallum & O'Connell, 2009; Villani, 2006) focuses on motivating and equipping leaders of color to work in a wide range of districts through better preparation, mentoring, and networking. A systems perspective addresses the problem and design solutions (Gates et al., 2019; Senge & Wheatley, 2001), focusing on all stages of the pipeline, to improve connections between segments and increase the "flow" of quality candidates of color into school and district leadership positions. Lastly, critical race theory supports the exploration of how implicit bias may hinder recruiting and retention efforts for aspiring leaders and hiring committees.

Integrating the Three Paradigms

While each paradigm offers valuable insights, the most effective approach to diversifying the leadership pipeline integrates all three perspectives. By combining these approaches, New York State can move beyond individual initiatives to create coordinated, regional, and statewide strategies that substantially increase diversity in educational leadership. This work requires sustained commitment from all stakeholders—state education departments, school districts, institutions of higher education, professional organizations, and community groups—working together to support the recruitment, preparation, hiring, and retention of diverse educational leaders.

The Town Hall discussions documented in this report represent an important step in this direction, bringing together diverse stakeholders from across New York State to share challenges, identify solutions, and build the relationships needed for long-term change. The recommendations that emerged from these discussions provide a roadmap for action at the district, regional, and state levels.

Epilogue: Initiatives in Other States

In concert with our Town Hall discussions and subsequent suggested role for state policy, we explored other states' K-12 leadership pipeline diversity initiatives. Two programs—in California and Massachusetts—support a range of strategies to build a more diverse leadership pipeline for school districts. Their efforts might serve as a model.

California's Diverse Education Leaders Pipeline Initiative

In 2023, California created a competitive grant program called the Diverse Education Leaders Pipeline Initiative program (SB 141 Section 112 (Chap. 48, Stats. 2023)). Its aim was to "...train, place, and retain diverse and culturally responsive administrators in transitional kindergarten, kindergarten, and grades 1 to 12, inclusive, to improve pupil outcomes and meet the needs of California's education workforce."

The state allocated $10 million to fund a variety of efforts for local education agencies (or consortium), with priority given to those that partner with higher education institutions. Funded efforts included:

- Coaching, training, and mentoring for current administrators and administrator candidates to serve and educate diverse pupil populations, engage diverse families, and support and retain a diverse educator workforce.

- Developing support systems for a diverse administrator workforce that reflects a local educational agency community's diversity.

- Paying for or reimbursing administrator program costs.

- Paying for or reimbursing administrator credentialing costs, including administrative services credential clear induction programs.

The aim of these initiatives is to remove barriers to entry into the K-12 leadership profession and to support candidates once they are in the pipeline.

Massachusetts' Educational Diversity Vision

In 2024, Massachusetts published its educational diversity vision which includes a strategic objective to diversify its educational workforce. Among their efforts were to create the Massachusetts Aspiring Principal Fellowship, a one-year mentoring program through the Lynch Leadership Academy for aspiring school leaders, whether teachers and other educators. The state also continues its Influence 100 Initiative, in partnership with the Barr Foundation, to provide 25 candidates and districts a two-year fellowship to "prepare for the superintendent role through monthly training and ongoing support in key aspects of the superintendency, with a particular focus on equity." Finally, to facilitate networking and statewide efforts to diversify the educational leadership workforce, the state also sponsors a semi-annual Partners in Equity Leadership Conference, for school and district leaders, higher education faculty and other interested educators.

References

Bartanen, B., & Grissom, J. A. (2023). School Principal Race, Teacher Racial Diversity, and Student Achievement. The journal of human resources, 58(2), 666–712.

Browne-Ferrigno, T., & Muth, R. (2004). Leadership mentoring in clinical practice: Role socialization, professional development, and capacity building. Educational administration quarterly, 40(4), 468.

Fuller, E. J., & Young, M. D. (2022). Challenges and Opportunities in Diversifying the Leadership Pipeline: Flow, Leaks and Interventions [Article]. Leadership & Policy in Schools, 21(1), 19-34. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2021.2022712

Gates, S. M., Baird, M. D., Master, B. K., & Chavez-Herrerias, E. R. (2019). Principal Pipelines: A Feasible, Affordable, and Effective Way for Districts to Improve Schools. Research Report. RR-2666-WF (978-1-977401-93-9).

Khalifa, M., Dunbar, C., & Douglasb, T.-R. (2013). Derrick Bell, CRT, and Educational Leadership 1995-Present. Race, Ethnicity and Education, 16(4), 489-513. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2013.817770

McCallum, S., & O'Connell, D. (2009). Social capital and leadership development: Building stronger leadership through enhanced relational skills. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 30(2), 152.

Miles, M., & Huberman, M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: A sourcebook of new methods. SAGE Publications.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2019). National Teacher and Principal Survey, United States Education Department. https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/ntps/summary/2019141.asp

New Leaders. (2022). Invest in Leadership: Five actions districts can take to increase school leader diversity. N. Leaders.

New York State Education Department. (2019). Educator Diversity Report Submitted to the Governor and Legislature of the State of New York.

Peña, I., Rincones, R., & Canaba, K. C. (2022). Forging Partnerships: Preparing School Leaders in Complex Environments. Journal of research on leadership education. https://doi.org/10.1177/19427751221133407

Perrone, F. (2022). Why a Diverse Leadership Pipeline Matters: The Empirical Evidence. Leadership and policy in schools, 21(1), 5-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2021.2022707

Sanzo, K. L., Myran, S., & Clayton, J. K. (2011). Building bridges between knowledge and practice A university-school district leadership preparation program partnership. Journal of educational administration, 49(3), 292.

Senge, P., & Wheatley, M. (2001). Changing how we work together. In Reflections. MIT Press for Society for Organizational Learning.

Steele, J. L., Steiner, E. D., & Hamilton, L. S. (2020). Priming the Leadership Pipeline: School Performance and Climate Under an Urban School Leadership Residency Program. Educational administration quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X20914720

Stony Brook University. (2025). NYSED Grant. https://www.stonybrook.edu/commcms/spd/edleadership/dei-grant/index.php

Thessin, R. A., Clayton, J. K., & Jamison, K. (2020). Profiles of the Administrative Internship: The Mentor/Intern Partnership in Facilitating Leadership Experiences. Journal of research on leadership education, 15(1), 28-55.

Turnbull, B. J., Worley, S., & Palmer, S. (2024). Strong Pipeline, Strong Principals. I. Policy Studies Associates & a. W. Foundation.